Under BC's Drinking Water Protection Regulation, small water systems have the option to use centralized or decentralized treatment systems. Choosing which system to use is one of the most important first decisions to make. It can be overwhelming to assess both alternatives; you’ll want to choose the treatment system that best helps you provide a long-term sustainable safe supply of drinking water at the least overall cost. In general, this will depend on:

- source water quality

- water demand (population served / # of service connections)

- treatment targets

- capital costs

- operator capability

- short term and long-term operating and maintenance costs

As each water source is unique, the selection of the type of treatment system should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis, in order to meet particular BC treatment objectives. You are encouraged to consult with the local Drinking Water Officer (DWO) and the regional Public Health Engineer (PHE) for help with determining an appropriate treatment process.

Centralized Water Treatment System

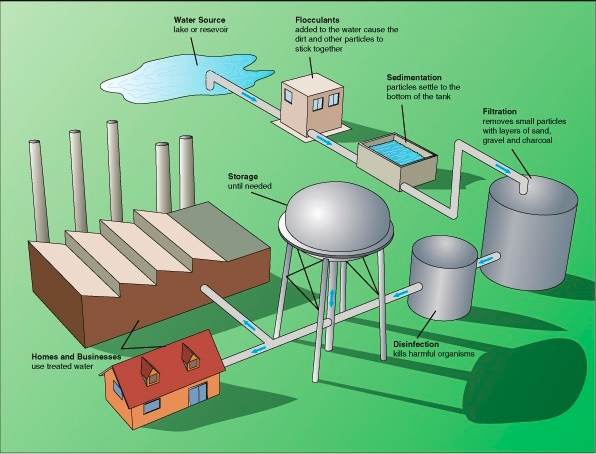

A centralized water treatment approach, also known as conventional treatment, uses a combined process of coagulation, flocculation, sedimentation, filtration, and disinfection. It treats water in a central location and then distributes water via a dedicated distribution network.

In urban areas, a centralized water treatment system can treat large volumes of water at high rates to accommodate all residential, business, and industrial uses. This approach is well developed and can effectively remove practically any range of raw water turbidity along with harmful pathogens, including bacteria, viruses, and protozoa.

However, the capital, operating and maintenance costs for a centralized treatment system can be significant. Centralized treatment capital costs include:

- water source development (e.g., a well, a lake intake, etc.)

- infrastructure construction (e.g., the treatment facility, the reservoir, the water mains, automated monitoring and control systems, etc.)

Centralized treatment operating and maintenance costs include:

- training and equipping onsite operators

- monitoring the water quality before treatment (raw untreated water)

- monitoring the water quality immediately after treatment and throughout the distribution system

- maintaining the water treatment equipment and the distribution system

Smaller communities can reduce costs by using a “package plant”, where treatment units are preassembled in a factory, skid-mounted and transported to the site where they are practically ready to operate. However, even with the use of a package plant, a centralized treatment system may still be financially out of reach for some rural communities.

Decentralized Water Treatment System

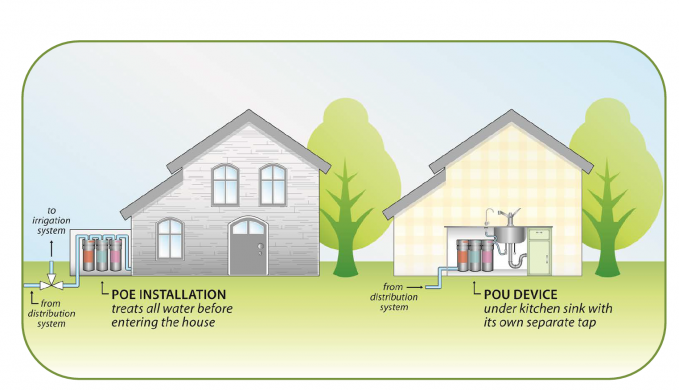

Water suppliers are required to provide drinking water from the water supply system that is potable (see Section 6 of the Drinking Water Protection Act). However, Section 3.1(a)(i) of the Drinking Water Protection Regulation (DWPR) provides an exemption for a “small system” (a water supply system that serves up to 500 individuals during any 24 hour period). This exemption states that a small system is exempt from supplying potable water to water users (i.e. homes and businesses) if each recipient of the water from the small system has a Point-of-Entry (POE) or Point-of-Use (POU) treatment system that produces potable water. This means that, for a small system, a water supplier isn’t required to provide potable water up to the home/business if each recipient (person) receives potable water from an approved POE/POU treatment unit. POE systems treat all the raw water entering the home/business (potable water is supplied to the entire household/business). POU systems are installed to treat water where needed, such as individual kitchen and bathroom taps.

For a small system, where a centralized community treatment system is unavailable or unaffordable, potable water can be provided by a decentralized treatment system (POE/POU) installed at the individual home or business. This provides an alternative to the construction and operation of a centralized treatment facility by permitting decentralized treatment for individual homes.

In some remote or rural areas, where the financial burden of installing a centralized system may be too great, or where there is no technical support, POEs/POUs may be the only treatment option. POEs/POUs are inexpensive relative to centralized systems because they defer large initial capital investments and reduce operating and maintenance costs. However, they are limited by their treatment capacity and capability for dealing with multiple contaminants. Also, POE/POU treatment is only practical from an operation and maintenance perspective if there is an appropriate manageable number of service connections.

BC Ministry of Health’s Small Water System Guidebook discusses POE/POE decentralized treatment and it states that this may be an option for a water supplier in the following situations:

- Where most of the total water supplied is used for irrigation or other non-potable use, and only a small quantity needs treatment.

- If a small water system supplier finds it is more cost effective than centralized treatment – generally for water supply systems with less than 40-50 connections.

- If there is a chronic chemical contaminant such as arsenic in the source water. In this case, they may also be used in combination with centralized treatment.

- If there is customer resistance to certain forms of conventional treatment.

POE/ POU systems are regulated and must have a construction permit before installation. They must also have an operating permit that includes monitoring criteria. Before approving decentralized treatment (i.e. POE/POU), regulators will require full community buy-in and monitoring. The operation and maintenance of individual POE/POU treatment systems are the responsibility of the water supply system.

Written agreements must be in place to allow the water supplier access to repair and maintain the POE/POU units at each home/business. Regulators will also require a water quality monitoring plan to ensure that the water supplier collects bacteriological samples periodically to verify that these devices are working properly. You will need to take these operation and maintenance costs into consideration if you choose a decentralized water treatment system.

Small Water System Guidebook, Province of BC, Ministry of Health (2024).

This guidebook is intended to be the first step in helping owners and operators find solutions to the challenges of operating a small water system, so you can provide the best possible drinking water to your customers.

Drinking Water Protection Act, [SBC 2001] Chapter 9, Province of BC

Drinking Water Protection Regulation (under the Drinking Water Protection Act), BC Reg, 200/2003, Province of BC

https://www.nsf.org/consumer-resources/articles/home-water-treatment Home Water Treatment from NSF

Obligations of the Water Suppliers of Drinking Water Treatment Systems that have Point of Use/Point of Entry Devices, 2014, within the Drinking Water Officers’ Guide (2022), Ministry of Health